Thetford’s trash and the long haul

Maybe “one of the best landfill sites ever considered in Vermont” has trash in its future after all.

Every year there’s a recurring line in the Town budget under the category of Dues -- GUVSWD - $28,468.

It pays for Thetford’s membership in the Greater Upper Valley Solid Waste District, known as GUV for short. Residents are probably most familiar with GUV through the April Big Trash Day where GUV takes items like mattresses, tires, broken furniture and the like, for a small fee. Residents’ disused electronics are collected in tandem. The latter are taken by Good Point Recycling so that circuit boards and other parts can be salvaged for reuse. A surprising amount of electronics are collected from Thetford, totaling 6,511 pounds (twelve fully loaded pallets) in September 2020 alone. GUV also holds two free Household Hazardous Waste collections a year at the Hartford transfer station and sells pre-ordered composters and kitchen pails at Thetford Academy at 50% of retail price.

But the $28,468 covers much more, and to understand it requires a dive into the history and origins of the Solid Waste District.

It began in 1987 when the State passed Act 78, effectively mandating the closing of the unlined landfills that were scattered throughout Vermont. Such landfills were just holes in the ground and had no barrier to prevent rainwater from percolating through the garbage and into the groundwater, flushing contaminants into potential drinking water. To tackle the proper disposal of solid waste, Act 78 placed a major emphasis on regional cooperation to take advantage of the economics of scale. It was simply too expensive for the average municipality to build and maintain a modern landfill with an impervious liner.

Thus eleven towns in our region—Bridgewater, Hartford, Hartland, Norwich, Pomfret, Sharon, Strafford, Thetford, Vershire, West Fairlee and Woodstock—came together and formed the Greater Upper Valley Solid Waste District. The District Charter was approved by the State in 1990. In 1991 they selected 38 possible landfill sites, 10 being in Hartland.

In 1992 a larger, bi-state solid waste group of twenty Upper Valley towns came together to solve the trash problem. There was a vision at the time of regional and bi-state cooperation. It included the GUV towns, plus Lebanon, Hanover, and a few other NH towns. Under the bi-state idea, Hartford would contribute its state-of-the-art recycling center. The operating landfill in nearby Lebanon would continue to take bi-state trash until its capacity was filled. Then GUV would open its landfill and take the region’s trash.

In 1993 GUV agreed to purchase 112 acres in North Hartland, “one of the best landfill sites ever considered in Vermont,” with the plan to buy more land in 1995 and 1998. However, rifts were surfacing in the bi-state alliance. Lebanon and Hartford considered taking control of their own trash disposal by buying GUV’s landfill site before GUV could obtain financing.

Shortly after, in 1994, Lebanon pulled out of the bi-state solid waste group, while GUV obtained voter approval to borrow $510,000 to acquire the North Hartland site.

Access to the proposed landfill had always been contentious. The original route was via South Main Street in White River Junction. While it was already used by Twin State Sand and Gravel to reach their quarry near the proposed landfill, residents strongly objected to existing truck traffic and the fact that the landfill would sharply increase it.

In 1995, the GUV Board of Supervisors again asked the voters to approve a bond for $175,000 for the purchase of 113.5 acres for an access road. Hartford pulled out of GUV in the same year. According to a Valley News article in March of 1995, the Hartford Town Manager asserted that Hartford would pay less for trash disposal if it withdrew from GUV. He predicted that if the GUV landfill was built, it would have to accept double the amount of trash projected, to keep tipping fees from soaring.

Despite the exit of Hartford that accounted for 30% of the GUV district’s population, residents of the remaining GUV towns voted in favor of the purchase.

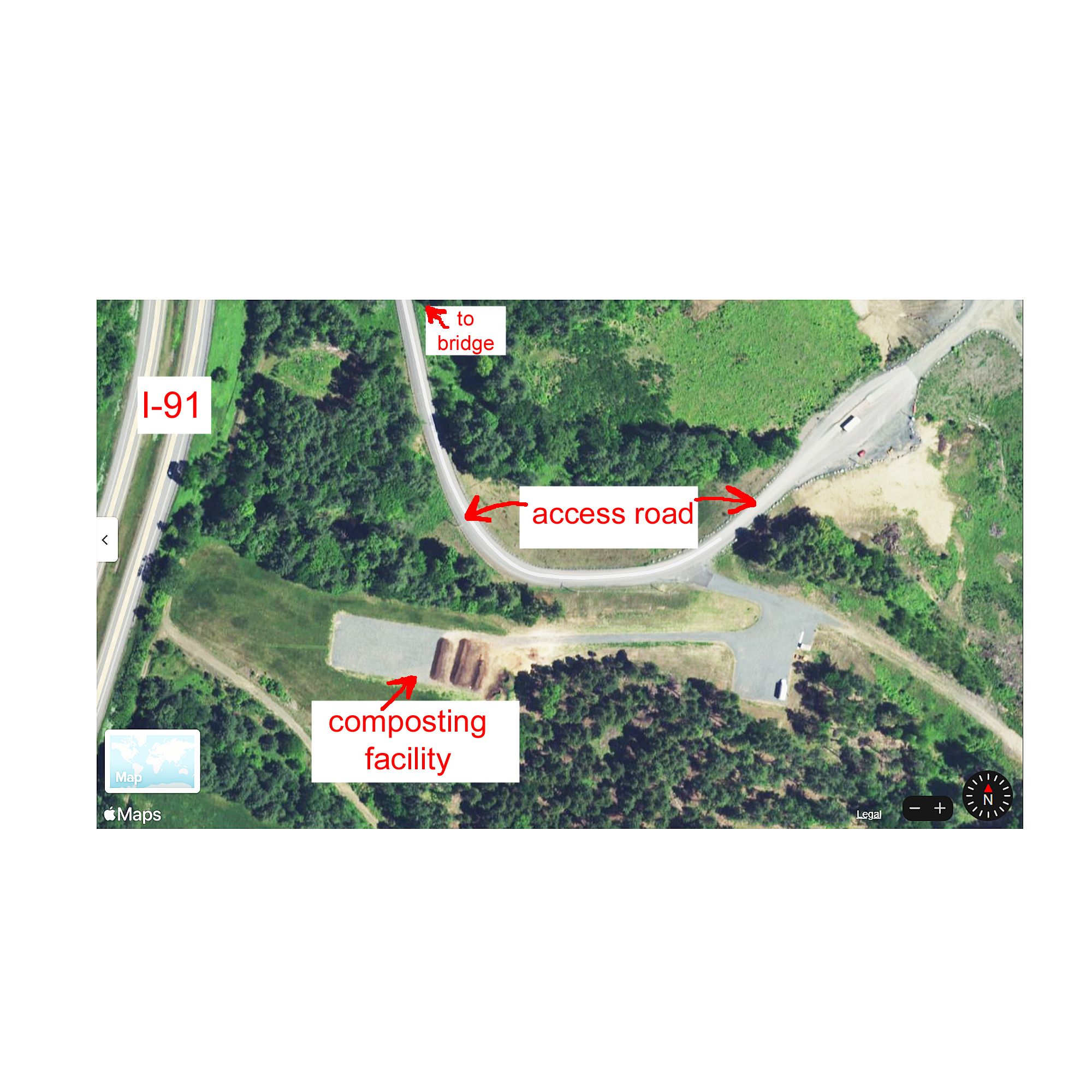

After the landfill won its Act 250 approval in 2004, the GUV board, in 2006, submitted a proposal for another bond, this time for the actual building of the access road. This led from Route 5 in Hartland to the landfill, via the construction of a new bridge across I-91. The bond was the biggest, $1.5 million. It passed with the approval of 55% of over 9,000 voters. Twin State Sand and Gravel reached an agreement with GUV in 2007 that allowed their trucks to use the I-91 bridge. This enabled them to avoid South Main Street in White River Junction, a route that was limited to 184 truck trips per day for 170 days a year, due to complaints from residents and the Town. This restriction had prevented the company from transporting the full amount of material they were allowed under their permit.

According to Fred Moody, then district executive director, the GUV bond paid for the I-91 bridge but not the access road. That was paid for by Twin State Sand and Gravel in return for a lien on the landfill property and permission for their trucks to use the bridge. According to a news article in 2009, the district owed $680,000 to Twin State Sand and Gravel.

That year saw a big debate over whether to contract with a private waste company to construct and operate the landfill. Proponents of the idea voiced concerns that the Lebanon landfill might shut out GUV towns as it approached the limits of its capacity, and GUV towns might be left with nowhere to send their trash. The proposed North Hartland landfill would be able to take GUV’s trash for up to 50 years. Furthermore, if it were opened by privatization, the decision would not be up to the voters, it could be a ruling of the GUV board of supervisors alone. The voters would only have had a say if GUV itself opened the landfill by financing it with an $8 million bond.

The city manager of Lebanon asserted that there were no plans to limit which towns sent trash to their landfill. The operation not only paid for itself but generated $600,000 a year for the city’s budget. The current “cell” of the Lebanon landfill had three years’ capacity left and there was one more cell permitted that would last another 10 years, and maybe two more future cells. Other opponents of opening the GUV landfill under private operation argued that it made no sense to have two competing landfills separated by a mile, on either side of the Connecticut River when one landfill was more than adequate for the region’s needs. In order for the GUV landfill to be commercially viable, it would need to collect far more waste than the 8,000 tons a year generated by GUV member towns. Because it would have cost about $8 million for one cell, it was estimated that 50,000 tons of trash per year would be needed to make operating the landfill feasible. With competition from nearby Lebanon, trash would have to be hauled from distant towns in southern and western Vermont, New Hampshire and as far away as Massachusetts.

In 2013 the Preliminary Landfill Design, Economic Analysis, and Waste Evaluation Study commissioned by GUV from CMA Engineers estimated that 75,000 to 125,000 tons per year would be needed in order for the landfill to make economic sense in light of potential capital and operating costs. According to the report, this translated into a four-to-six year capacity.

Ultimately the board did not go forward with opening the landfill, choosing instead to “place the asset in reserve for development when it is needed” as stated in their Implementation Plan dating back to July 1999. In 2015 GUV discontinued its permit for the conceptual landfill design and revoked its site certification before its expiration.

What of the landfill site today?

Tom Kennedy, Executive Director of the Mount Ascutney Regional Commission, reports that the GUV district has been working hard to attract other enterprises to the North Hartland property to generate revenue. An opportunity arose with the passing of Act 148, also called the Universal Recycling Law, which took full effect in 2020. Organic yard waste, leaves, woody debris, and food scraps may no longer be thrown in the trash. This mandate, coupled with recycling of plastics, paper, and metal, was predicted to reduce the waste thrown into landfills by 50% and significantly relieve Vermont’s solid waste problem. This set the stage for GUV to lease 3.3 acres of their site to Grow Compost, headquartered in Moretown, VT, to house a small-scale composting operation that opened in 2018. GUV is also in the process of leasing a much larger portion of the site to Norwich Technologies for a 500kW solar panel array. The company has applied to the VT Public Utilities Commission for the necessary permits. GUV is now negotiating with Norwich Technologies to develop a 2.2 MW facility, over four times the output of the first proposed array. Three-phase electrical service will need to be brought to the site at no small expense so the solar electricity may be fed into the grid.

The question sometimes comes up “Can we withdraw from the Solid Waste District?” The answer, theoretically at least, is “Yes.” But note that the District’s Charter includes the wording, under the Section dealing with a town withdrawing from the District: “It shall be a condition that the withdrawing municipality shall enter into a written agreement with the District whereby such withdrawing municipality shall be obligated to continue to pay its share of the debt incurred by the District for the remaining bonding or contract term.”

Thetford’s remaining debt will be paid off in 2029. The Lebanon landfill continues to take trash from towns in the GUV district and has plans to create another cell. However Thetford GUV representative Jim Masland anticipates that the Lebanon landfill has about 20 years before it is full and cannot expand any further. That is about the predicted lifetime of solar panels. So maybe “one of the best landfill sites ever considered in Vermont” has trash in its future after all.