Thetford's tax rate is above average, and it matters

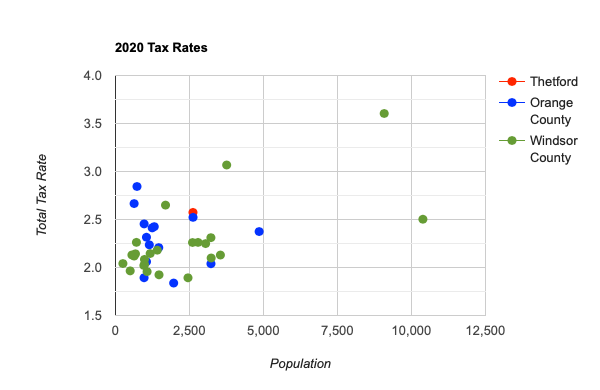

In 2020, Thetford had the sixth highest tax rate in two counties.

Last budget season, at least two sitting Selectboard members expressed the sentiment that property tax rate increases don’t impact taxpayers as much as we think because of Vermont’s Property Tax Credit: “You may be eligible for a property tax credit on your property taxes if your property qualifies as a homestead and you meet the eligibility requirements. The maximum property tax credit is $8,000.”

The eligibility requirements referred to include that: the property qualifies as a homestead and the property owner has filed a Homestead Declaration for the current year; the property owner was domiciled in Vermont for the full prior calendar year; the property owner was not claimed as a dependent of another taxpayer; the property owner claimed the property as their homestead as of April 1; and the household meets the income criteria. In 2020, the maximum qualifying household income was $138,500.

The way the credit is calculated is complicated, but for those who qualify, an increase in the local tax rate can indeed be offset by the credit, especially for those households earning less than $47,000/year. The apparent intention is that property taxes do not exceed a set percent of household income for low- and moderate-income Vermonters.

While landlords cannot claim the credit for their rental properties because they do not qualify as homesteads, renters are able to claim a renter’s rebate. This has a similar apparent intention and criteria as the state’s property tax credit. If landlords raise rents because their property taxes increase, then tenants whose households are earning less than $47,000 can be insulated from that impact.

Looking more closely however, $47,000 is two times the annual gross income of a Vermonter earning minimum wage who works 40 hours a week and 50 weeks a year (full time). That means that any tenant household with two full-time income earners does not qualify for the renter’s rebate if one of those earners is making even a penny more than Vermont’s minimum wage. Meanwhile, two wage earners who own a home still qualify for the property tax credit up to a household income of $138,500. In addition, the maximum renter’s rebate is capped at $3,000, compared to the $8,000 for property tax credits for homeowners. This means that low- and moderate-income Vermonters are given more financial support by the state if they own a home and less if they rent. Thus renters are among the most vulnerable of demographics when it comes to property tax increases over time.

It is not difficult to see why tenants struggle to prepare themselves financially for home ownership, including saving for a down payment. They receive less help, and the rent money they spend on housing is not building any equity. They’re often spending more on housing-related expenses than their home-owning counterparts. As I recently wrote, it’s difficult to buy your first home without some assistance, but there’s more to it. Most of the homes that young, first-time, and/or low-to-moderate income homebuyers can afford to purchase have often been sitting vacant or were previously rental properties, which means they typically weren’t filed as homesteads in the year they were sold. The homebuyer therefore pays the full property tax burden at closing, even if they would otherwise qualify for a property tax credit. And even if those taxes are prorated, the proration usually starts on the fiscal calendar (July 1), not the calendar year (the Town of Thetford is on a calendar year), meaning the homebuyer who has a purchase date of late summer or early fall (which is most common) is still paying the lion’s share of property taxes at closing.

Since the property tax credit is dependent on the previous year’s homestead declaration, the homebuyer will pay the full property tax burden in the next year as well (assuming they purchased their house after April 1, which is most common). That means the property tax credit is not helping people when they buy their house or in the first year after they move in, which, assuming they are eligible for the maximum tax credit, could carry a financial burden of $16,000 that settled homeowners do not have to pay. That’s a big deal, since the types of homes that first-time buyers can afford are typically not so well-maintained. Often there is deferred maintenance to catch up on, such as replacing cracked windows and broken appliances, remediating mold and asbestos, re-plumbing the house, replacing or repairing a failed septic, or bringing electrical wiring up to code when corroded ground wires are found.

It’s fair to say that homeowners in their first and second year of ownership are also in the most vulnerable demographic when considering those impacted by property tax increases, but there are others. Those living on fixed incomes above $47,000/year are ineligible for the tax credit as it applies to municipal taxes. That is, the credit only applies to education (homestead) taxes for households earning more than $47,000/year. This means that increases to municipal taxes are felt by those living on fixed incomes if those increases exceed increases such as inflation adjustments made to social security payments. In other words, their spending power decreases. The spending power of middle-income households also decreases if their household income (for example, wages) does not keep pace with increases in municipal taxes.

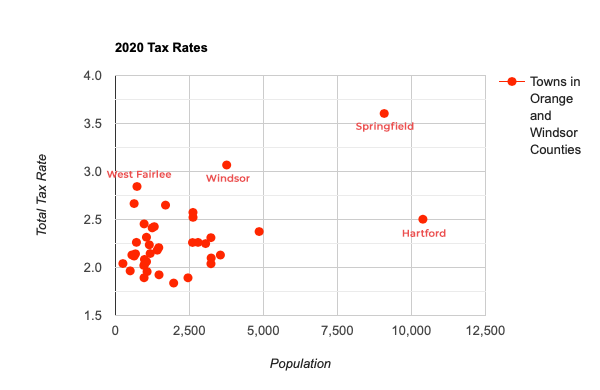

Vermont is criticized for its high property taxes, but those taxes can vary by town. You might think that taxes are higher in towns that are perceived as wealthy, or in larger towns that provide more services and have more infrastructure, or even in smaller towns that have a smaller tax base supporting the same basic functions of local government. I put the tax rates (combined homestead and municipal) of every town in Orange and Windsor Counties on a scatter graph and compared that to their population to look for a trend... any trend.

There are two outliers with larger populations: Hartford and Springfield. And there are two outliers with tax rates above 3.0: Springfield and Windsor. Most of the towns, however, have tax rates below 2.5, whether their population is several hundred or several thousand. The town with the lowest tax rate is Newbury. The highest tax rate, after Springfield and Windsor, is West Fairlee.

As a random sample, Brookfield, Norwich, Sharon, Woodstock, and Williamstown all have tax rates between 2.0 and 2.2. Perhaps there is no obvious trend.

So where does Thetford fall in all this?

In 2020, Thetford had the sixth highest tax rate in the two counties, behind Bethel, Springfield, Windsor, West Fairlee, and Vershire. The only other town, other than Hartford, with a tax rate higher than 2.5, and filling out 7th place, is Bradford.

This means that a homeowner is paying more in taxes to live in Thetford than they would in 35 other towns in the region. It might be easier to find a more affordable home in Thetford than Norwich, for example, or Fairlee than Thetford, as you move further from the regional center, but once you find and buy that home, you’re financially better off in terms of property taxes in almost any other town than Thetford.

There are a lot of factors that go into buying a home: where you can find something in your price range, what kind of community you want to live in, and how far you are willing to commute. Regardless, the impact of increasing taxes on vulnerable populations should be understood, especially in towns where taxes are already well above average.