Real Organic tomatoes from a state-of-the-art greenhouse in Thetford

Vines can easily reach 50 ft in length.

Longwind Real Organic tomatoes are a recognized brand that's available in many stores throughout the Northeast, in food co-ops from the Hanover / Lebanon / White River group all the way to Brattleboro and Concord, as well as in chain supermarkets like Shaw’s and Hannaford.

Dave Chapman, who started it all, never intended to focus on intensive tomato culture. Back in the late 1970s, he began growing vegetables with a pair of oxen on one acre beside Route 113 in Thetford. He drew on a year of experience working with celebrated organic farmer Jake Guest of Kildeer Farm in Norwich and sold at a roadside stand and the newly founded Norwich Farmers Market. After a couple of years, he was able to buy "the back field" at Longwind Farm's present location in East Thetford and, eventually, the "front field," too. The oxen gave way to a small tractor, and at his peak Dave was cultivating five acres of vegetables and flowers.

The arrival of children changed all that. In the first year of being a parent, the farm income plummeted. Growing 100 different varieties of vegetables came at the price of a 60-70-hour work week. Maintaining that pace was just not compatible with being part of his children's lives.

Luckily, Dave was already growing tomatoes with success in heated plastic hoop-houses. In fact, people would line up for his tomatoes at the start of the season. To the great disappointment of many customers for whom Longwind Farm had become their go-to for organic produce, he made the decision to transition to growing only tomatoes.

Dave made the switch from plastic to a glass greenhouse. But he kept on growing tomatoes in soil, unlike his European (and later US) counterparts who grow greenhouse tomatoes year-round by hydroponic methods. He learned everything he could, including a visit to observe first-hand the methods of Dutch tomato growers, the most sophisticated greenhouse growers in the world at the time. He also received advice, books, and friendship from Eliot Coleman, a researcher, author, educator, and organic farming pioneer who lived in Vershire. From Coleman he absorbed organic methods for maintaining soil health that rely not only on high organic matter but also a diverse and teeming microbial population. Once Dave’s greenhouse was up and running, a Dutch consultant advised him on creating the correct greenhouse climate, how to raise young tomato plants, and how to prune and train the growing vines. But Coleman was the go-to for soil.

People may wonder if there are benefits to consuming organic rather than conventionally grown vegetables beyond avoiding pesticide and herbicide contaminants. And aren’t organic hydroponic tomatoes equivalent to organic soil-grown tomatoes?

Regarding organic vs. conventional agriculture in general, the mass production of crops on an industrial scale comes at a huge cost to soil and river health. When soils are farmed constantly without determined efforts to maintain organic matter and soil structure, they become depleted and run down. As soils are depleted, greater and greater amounts of artificial fertilizer must be added to keep up crop yield.

Fertilizer run-off from intensive farms loads streams and rivers with excess nitrogen and phosphorous, resulting in algal blooms, fish kills, and unhealthy rivers. Thirty percent of US streams and rivers suffer from high levels of nitrogen or phosphorus. The last 50 miles of the Mississippi River are so heavily polluted that there is now a large dead zone where the river flows into the Gulf of Mexico. This year, the dead zone is the size of New Jersey — about 6,700 square miles. Severe health problems are also associated with leaching of fertilizers into drinking water, as documented in the Midwest. Pesticide pollution is another serious issue, although it has been overshadowed by the magnitude of the fertilizer problem.

Regarding the debate about organic tomatoes grown in a hydroponic system vs. in soil, almost all tomato greenhouses in the US — organic and conventional — use hydroponics, accounting for 30% of all fresh tomatoes sold. Longwind is an oddity for growing in soil. Dave is frustrated that the USDA now allows hydroponic tomatoes to be labeled “organic” if the hydroponic fertilizer inputs can be argued to be “organic in origin.” The complexity of a living, organically farmed soil cannot be duplicated in a simplified hydroponic cocktail. For instance, when plant roots grow in soil, about 25% of photosynthetic production is put into root exudates that are a complex cocktail of sugars, amino acids, lipids, flavonoids, terpenes, enzymes, and hormones. There’s a reason plants put so much resources into this — it attracts and feeds soil microbes that, in exchange, provide minerals, defense compounds, micronutrients, etc. to the plant. Dave asserts that this complexity contributes not only to plant health but also to the health of those who eat the plants and, just as importantly, to flavor. He uses liberal amounts of compost to feed both plants and microbes. The beds are tilled once a year to aerate them and redistribute organic matter. Otherwise it’s up to the roots and the microbes.

Today Longwind Farm is an impressive, state-of-the-art facility that employs 25 workers including a business manager. Approaching one of the vast greenhouses, one is struck by the long line of lazily turning fans. The roof sports a triangular structure that carries revolving brushes to clean the glass.

On a sunny day, the fans do the work of cooling the greenhouse because it is important to keep the temperature fairly constant. Temperature swings encourage diseases like mold and fungus infections. In the winter, hot water pipes running along the ground between beds maintain the temperature, and incoming fresh air is warmed by heat exchangers.

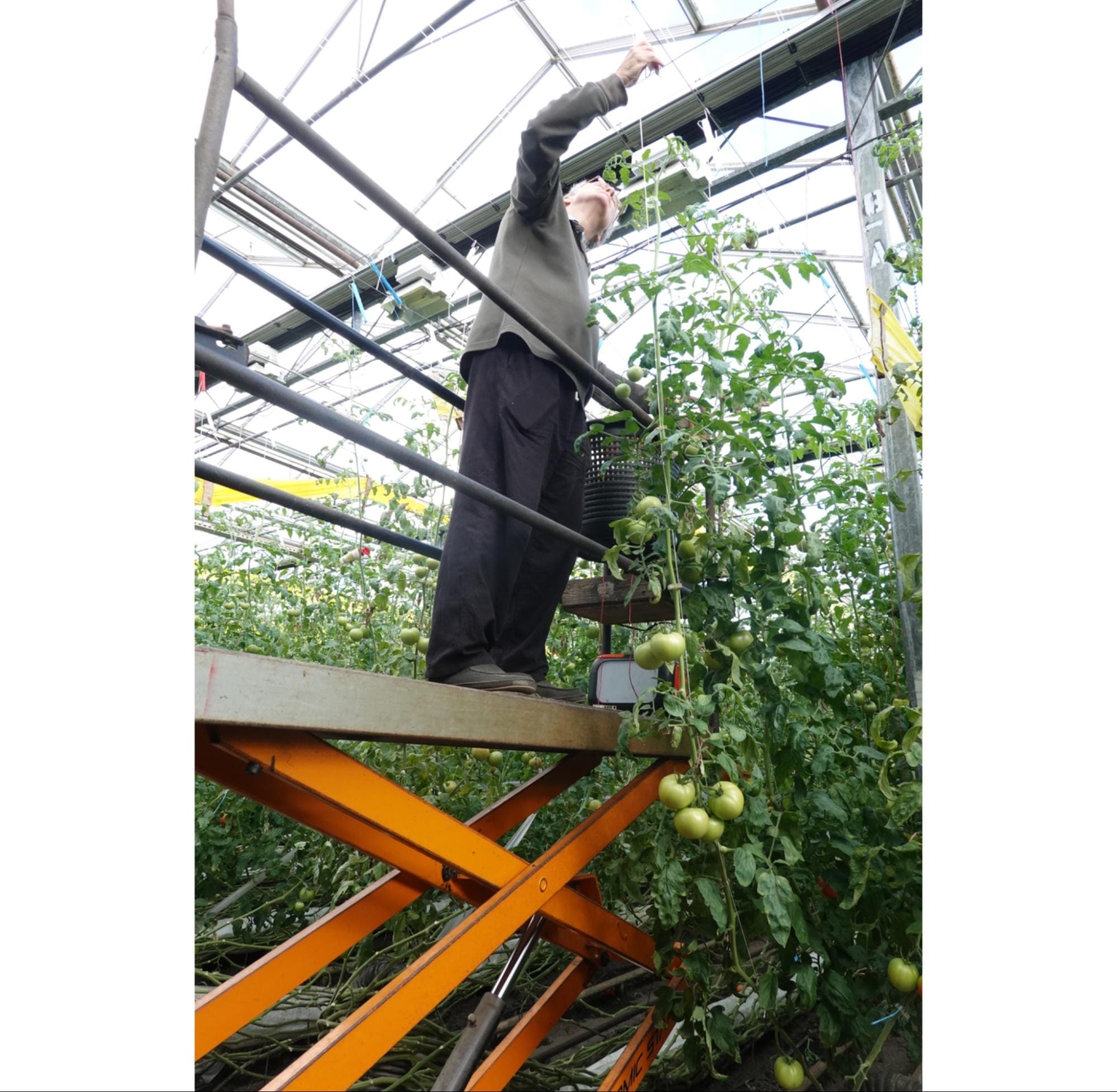

The tending of the tomato vines is done by hand, often from platform lifts as the plants almost reach the greenhouse ceiling.

Each of the roughly 11,000 plants in a greenhouse is supported by a cord with which the top of each vine is moved periodically so that the lower, leafless part is trained along the ground.

Vines can easily reach 50 ft in length. Side branches and lower leaves are carefully pruned away to allow good air circulation, critical for avoiding fungus outbreaks. Watering is through drip hoses resting on the soil since wet leaves are a recipe for disease.

Greenhouse pests like whitefly and aphids are controlled by releasing predatory insects and mites.

Tomatoes are the major greenhouse crop in the US. At a large commercial operation, one greenhouse can cover 20 acres.

By comparison, Longwinds is tiny. It is a labor of love, a living proof that intensive greenhouse growing can still be organic and can still maintain the health of the soil, the crux of organic farming. That’s why Dave’s tomatoes carry the Real Organic certification in contrast to USDA Organic which allows hydroponics and some synthesized fertilizers and pesticides under its label.