North Thetford water companies - between a rock and a hard place

At this point the state has not come down hard on North Thetford to force compliance — yet.

Some time before the year 2000, the Vermont Department of Environmental Protection (DEC) finalized rules that governed Wastewater and Potable Water supplies.

The goal of the rules —“…to regulate water systems in the state so that they provide clean and safe drinking water to Vermont's citizens” — seemed straightforward, admirable even. The Rules continue: ”A Public Water System means any system(s) or combination of systems owned or controlled by a person, that provides drinking water through pipes or other constructed conveyances to the public and that has at least fifteen (15) service connections or serves an average of at least twenty-five (25) individuals daily for at least sixty (60) days out of the year." For small water companies in villages, things from that time on have been anything but straightforward.

Take North Thetford, for instance. Before the advent of Rules, the community was served by two water companies, Union and Village. They provide upkeep of the water systems in return for annual fees from the users.

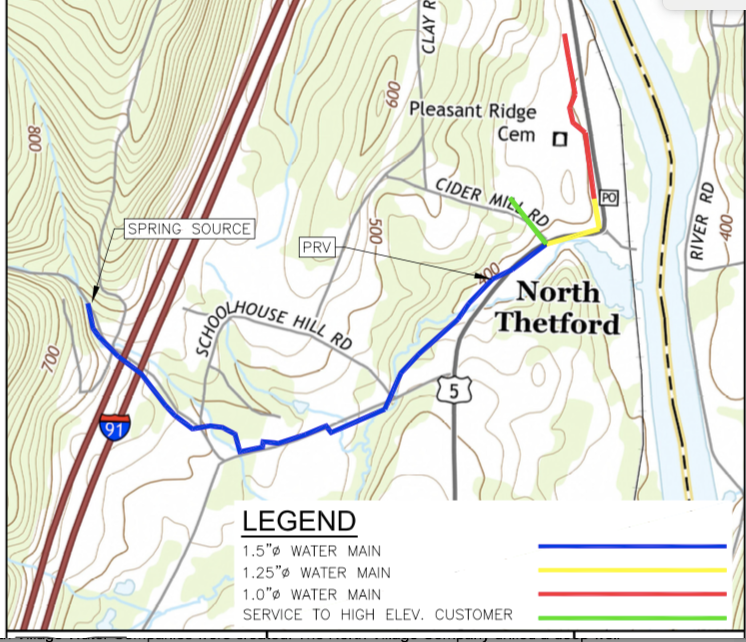

The Union Water Company draws its water from a spring by the bed of a hillside brook on the far side of the interstate, a short distance from the end of South Turnpike Road. The original spring, probably dating back to the 1920s, had been a very dependable source of water. However in the 1960s it turned out to be in the right-of-way for the incipient I-91. The current spring location was donated by Edward Clay, a farmer who knew that terrain well and had scouted the area for reliable water for his cows. His brother, Ernest, who was the president of the Union Water Co., felt that the spring could supply the whole of North Thetford. It had already supplied his small dairy farm and the village. The pipes themselves needed to be replaced on occasion. One time was in the 1960s when the interstate was built. Then lead water pipes fell out of favor in the 1970s, leading to a major replacement. Pipes were again replaced in 2017 after a ferocious rainstorm washed out Turnpike Road down to bedrock. Through all this, the spring has faithfully provided clear, clean water, despite various droughts — notably the 71-week drought beginning on June 23, 2020, and ending on October 26, 2021.

The Village Water Company, now the South Village Company, draws its water from the bed of the same brook, but closer to the Connecticut River. The springhouse sits in the corner of a field on Latham Road near the Schoolhouse Road junction.

Springs do not gush a torrent of water, they provide a small but steady stream. Therefore every home on these spring-fed water supplies was equipped with a pressure booster pump and a concrete cistern in the basement that holds enough water for about three days. This is still a common setup in rural Vermont, even for new homes.

After the adoption of the Potable Water Rules, the state Water Supply Division imposed regulations on public water supplies with 15 or more connections. Village Water Co. had 18 users. They decided to split into two water companies with nine users each, thus avoiding regulation. And so the North and South Village Water Companies were created. The North Village Company drilled a deep well near the cemetery. But although it was deep, it did not supply enough water, even after it was treated with fracking to open up seams in the bedrock. Another well was drilled between the North Thetford Church and the Connecticut River. This did supply enough water, but apparently it has undesirable nitrates in the water that require filtration.

The Union Company, with approximately 24 users at the time, decided it had no choice but to be regulated. Then they found the state viewed cisterns with suspicion, as possible sources of contamination, even though they were reliable and trouble-free.

Furthermore, the state decided that the Union Company should increase their water pressure. But, to determine whether the water pressure really was too low, the state required a hydraulic analysis performed by a licensed engineer. This study cost the Union Company half a year’s worth of revenue. The state demanded that the water pressure from the spring be raised to 60 psi (pounds/square inch). This is actually impossible with the current pipe from the spring, which is 1.5 inches in diameter, narrowing to 3/4 inch for the last ten users. To keep cisterns topped up it is perfectly adequate. To achieve the 60 psi pressure, about 9,000 ft of pipe would have to be excavated and replaced with a 4-inch pipe. That pipe, and that amount of pressure, would be complete overkill considering the tiny number of users served.

The state then called for another study to show how all the cisterns and pumps could be replaced. The second study cost another year of revenue. The upshot - to modernize the system, the company would have to spend $500,000. That amounts to about $25,000 per individual user.

In the meantime, the state began requiring cistern owners to document that they had taken measures to prevent back-flow, by creating a 2-3 inch air space between the end of the pipe from the spring and the cistern water. In addition, a drain between pipe and cistern must be added.

However, it is unpaid volunteers who run these community water companies, and volunteers have no power of enforcement. While many users are compliant, among the non-complying it appears that only two users have made the required changes. Even when residents had to replace their cisterns, the plumbers involved did not install the drains, perhaps deeming them superfluous.

Those who manage the water companies observe that all this expense and analysis have done nothing for the actual quality of the water.

So, the water companies find themselves between a rock and a hard place. Should the Union Company knuckle under and look for a source of funding, most likely a large loan, to comply with regulations that are more appropriate for a ski area? Or should individual users drill costly private wells and abandon their water company? In-village lots are small, and there are on-site septic systems, local landfills, salted roads, etc, that mean permits to drill many of those wells would be denied. Or should the Union Company stay in the 1950s by splitting up to escape regulation? That does not seem a viable option either. The largely elderly users in all three companies need to maintain the underground pipes — over a mile in the case of the Union Company. Gone are the strapping young farmers who could dig in the mud and fix things when they broke.

At this point the state has not come down hard on North Thetford to force compliance — yet. And, who knows, maybe the incipient Water Study Planning Grant will point a way forward.