Forest health and deer — Bambi has to go

Deer are over-grazing forests in the Northeast, including Vermont... and Thetford.

A stroll through the forest is one of the pleasures freely available to Upper Valley residents. Indeed, Thetford boasts many nice woods trails on both public and private land.

Superficially the woods look great, lush and green as a result of this summer's heat and plentiful rain. But a closer look reveals something not quite right. Examine the forest canopy. The mature trees represent a diversity of species, in particular sugar maple, red maple, black cherry, red oak, white ash, yellow birch, gray birch, and hemlock to name some of the commonest. Now look at the understory and what you find is predominantly — even exclusively — beech.

What we see is the fallout from white-tailed deer overpopulation. Deer are equipped to be selective browsers. Narrow heads and long slender tongues allow them to reach into vegetation and pick out just what they like. A large part of their diet is young tree leaves and tree buds, and favored trees include maples, oaks, and white ash. Beech is one of their least favorite food species, as is hornbeam.

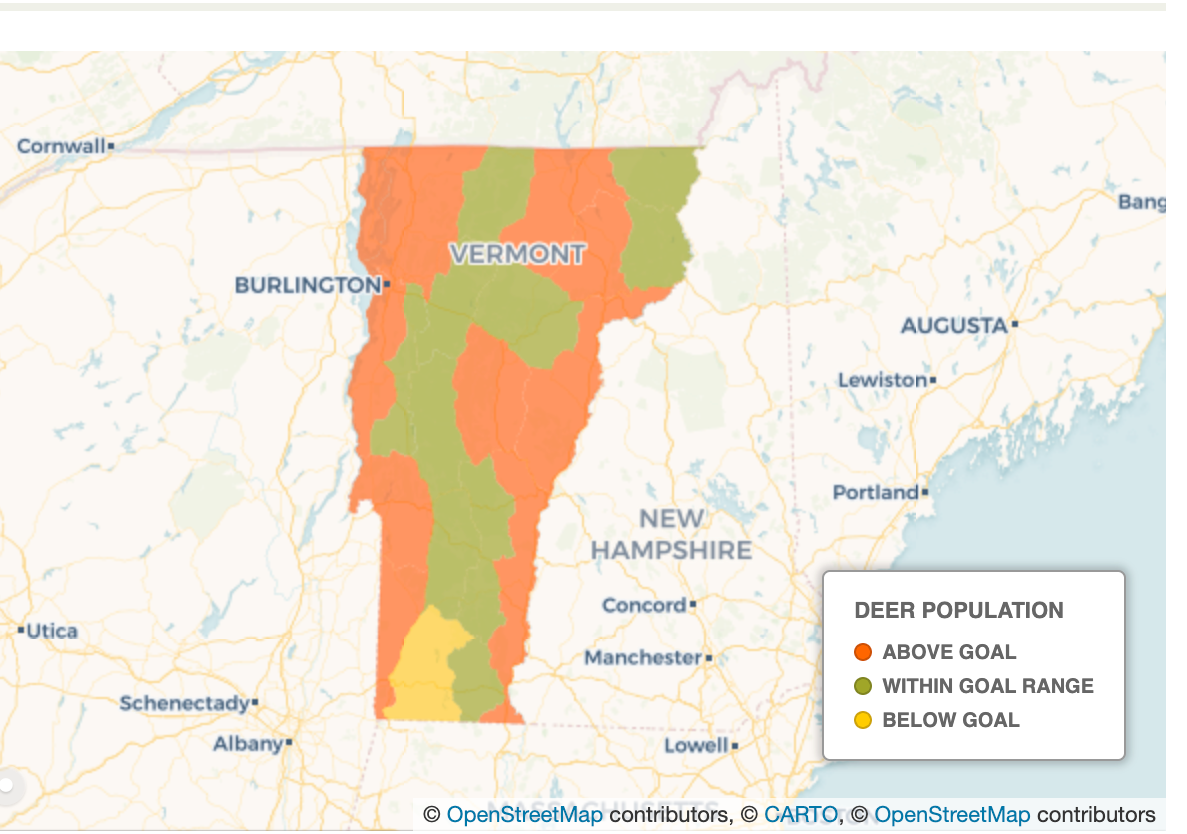

Seedling trees make for easy forage, and browsing by an overabundance of deer stops the reproduction of most hardwood trees except beech, decimating forest diversity in many areas. An average deer eats over 4,000 tree seedling tips in one day. Even at 12-18 deer per square mile — the "preferred density" for deer, according to the VT Department of Fish and Wildlife — it's not hard to see why forest diversity has plummeted. And deer exceed this preferred density in large swaths of the state, including Thetford and Orange county (see map).

For landowners with timber holdings, this is proving to be disastrous. Oak, maple, cherry, and ash are valuable timber trees. Vermont's Current Use program was put in place so that landowners would provide a steady supply of timber for Vermont's forest products economy. But after a timber harvest, these desirable trees don't regenerate anymore. Due to excessive deer browse, beech becomes predominant, but this species is afflicted by beech bark disease, now endemic in Vermont. It is a complex disease, the product of scale insect attack followed by fungus infection, but the important point is it reduces the economic value of the re-grown timber stand, with dramatic shifts to younger and smaller beech trees that eventually succumb to the fungus.

One other factor is that deer don't eat invasive woody plants like barberry, buckthorn, and honeysuckle Nor do they eat invasive goutweed or garlic mustard or native hay-scented fern. These aggressive plants grow in shade or sun and, in combination with deer browse, effectively out-compete native tree seedlings.

And there is more at stake than valuable timber tree species. A comparison of two inventories of ground-level vegetation in a Pennsylvania forest, taken 70 years apart, showed an 80 percent reduction in the number of wildflower species, herbaceous plants, and shrubs from deer browsing. In the 70 intervening years, deer density had increased from under 10 to over 30 per square mile. Spring wildflowers like trillium were only found in places that deer could not reach.

The effect of deer does not stop there. Bird lovers take note. A report by the Audubon Society describes the effect of fencing deer out of an area of a forest sanctuary that was under deer pressure and struggling to regenerate after a timber cut. Within a short time Chestnut-sided Warblers, Eastern Towhees, and Indigo Buntings appeared within, but not outside of, the fenced area. Multiple species of trees that were absent from the rest of the sanctuary sprang up in the enclosure, and both Black-throated Blue and Black-throated Green Warblers, not seen in the rest of the sanctuary, moved in.

Another study found that high deer density reduced the overall abundance of forest midstorey birds by 37 percent, and the number of bird species by 27 percent. Five bird species became locally extinct in the study area when deer density reached 20 or more per square mile. Some birds are especially vulnerable. The Cerulean Warbler prefers to nest in white oaks, among the favorite foods of deer. Its population has declined by 63 percent in the last 50 years.

Plants great and small are the life support systems for all animal species. The smallest forest animals that feed on trees — insects — play an outsize role in the food chain. Insects are the engine that transforms plant material into nutritious animal proteins and fats. They are eaten by a multitude of other animals, particularly birds. The majority of songbirds feed their young on caterpillars; think of them as a soft, juicy food packet that's easy for a baby bird to swallow. Painstaking observation showed that a single pair of Chickadees feed their young 6000-9000 caterpillars prior to fledging. Forest trees support huge numbers of caterpillars of different moths, each species finely tuned to eating one or a very few tree species. Oak trees alone are hosts to caterpillars of 532 moth species, cherry to 456 species. A diversity of trees is crucial to guarantee this food source. When a forest is reduced to mostly beech (that support only 127 caterpillar species), the caterpillar supply becomes vulnerable. A disease that defoliates beech trees would be devastating.

Cornell University ecologist Bernd Blossey writes that "The forests of the Mid-Atlantic and the Northeast are in imminent danger of collapse" under the mounting pressure of deer overpopulation. In addition, we lose more than $100 million per year in agricultural crops eaten by deer and endure about 60,000 injuries and 400 deaths per year in deer-related vehicle accidents.

Deer multiply their numbers because humans have extirpated large predators from the landscape. Recreational hunting is not enough to keep deer in check. Moreover, the increased posting of land by newcomers to prohibit hunting, hand in hand with the ongoing fragmentation of forests by rural suburbanization, all work in favor of deer. Housesite clearings, forest edges and home gardens provide favored browse, and deer soon learn that homeowners are nothing to fear. Reducing the herd by employing sharpshooters can be effective (and the meat is given to food banks, not wasted) but it takes multiple years and is often stymied by public sentimentality and ignorance.