Decorative wreaths of — human hair

Victorian-era hair wreaths are on display at the Thetford Historical Society.

People will soon mark the winter festive season by decorating homes with wreaths of evergreen branches. The wreath probably originated as a use for trimmed Christmas tree twigs. However, it became a symbol of eternal life because evergreens stay green through winter and the circle represents divine perfection.

Victorians took wreaths in a different direction. They made wreaths out of human hair. This art of hair work had its origins in England during the 1600s as a way to mourn and commemorate the deceased. From the 1830s onward, this cultural practice blossomed and was further popularized by Queen Victoria, who presented her children and grandchildren with jewelry made from her hair and undertook a forty-year long period of mourning after the death of Albert in 1861 at age 42. The practice of wearing black clothing to mourn the dead and giving hair keepsakes swept through the British middle classes and other western countries, including the U.S. Hair wreaths were even made in Thetford, as evidenced by the display at the Thetford Historical Society in the Latham Library on Thetford Hill.

Epidemics of various diseases and the lack of science-based medical practice meant that death was ever-present. Infant mortality, in particular, was high. Royalty always traveled with a set of mourning clothes “just in case.” The focus on death with elaborate mourning customs and etiquettes reached new heights in the Victorian era with customs particularly centered on women, since domestic life revolved around them. Birth and death usually took place at home.

For those who could afford it, mourning imposed a strict dress and behavior code that was capitalized upon with the rise of manufacturing. Mourning attire for women, in the form of bodices, skirts, bonnets, capes, veils, and the like, became a huge commodity market. Women’s magazines offered advice on mourning etiquette for different types of bereavement. A widow should wear mourning dress for two and a half years, and veil her face when in public. She should also refrain from attending balls and other “frivolous” events. After a year, simple jewelry was allowed, mostly black, for instance, jet stones in brooches, earrings, and rings. In the second year, dull colors like gray and subdued violet could be worn. It was considered inappropriate and cold-hearted to omit the observance of these traditions; however it was also improper for a woman to overdo her expressions of grief.

In public women in mourning were obvious and, thus, were treated with consideration and gentility. This helped to boost the popularity of mourning practices. In private women compensated for their diminished social activity by making hair wreaths and hair jewelry, which also counted as an expression of mourning. Possessing a piece of jewelry or art that contained a physical piece of a loved one was a tangible form of grieving and expressed the important Victorian virtue of sentimentality.

Indeed, middle-class women learned the skills needed to thread hair wreaths when they learned the feminine crafts of needlework and embroidery.

To help with the weaving, special circular work tables with an open center could be obtained. A handbook from 1867, the “Self-Instructor in the Art of Hair Work,” provided detailed diagrams and patterns for braided and beaded hair jewelry designs. For memorial wreaths, incorporating an open end at the top was symbolic of the deceased ascending to heaven. Other accounts describe this horseshoe shape as bringing luck.

When it began in the 1600s, hair work was small in scope, like a lock of hair in a brooch or ring. With the 1800s came the Romantic movement and displays of sentiment, including grief, that were more dramatic. Hair work pieces became large and elaborate, including fashionable necklaces, bracelets, and wreaths.

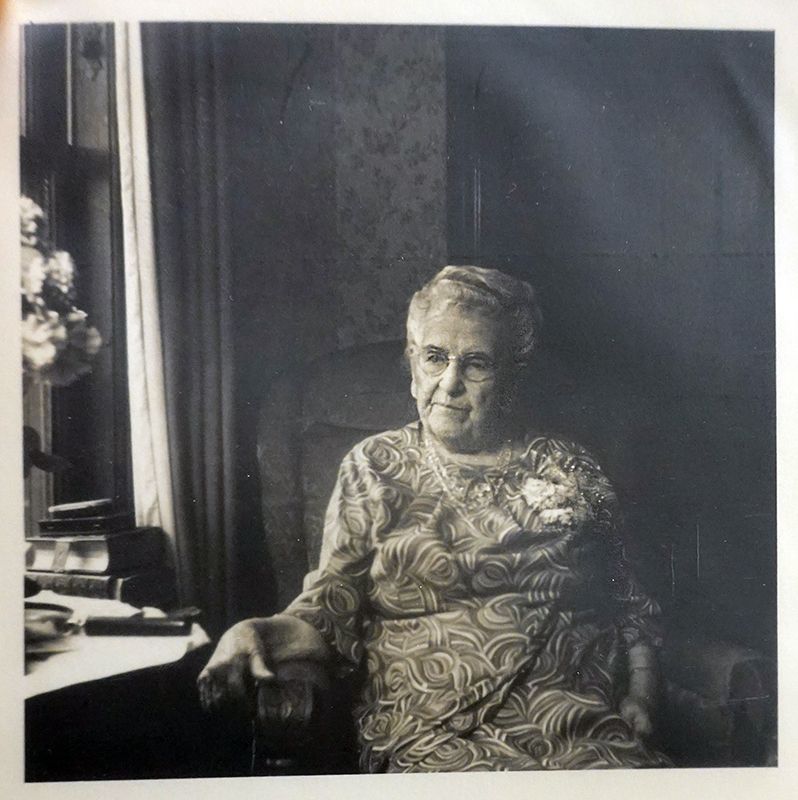

As this art form evolved, wreaths were not necessarily made to commemorate a deceased family member. They were created for sentimental reasons and given as gifts to friends or loved ones. For instance, one of the hair wreaths at the Thetford Historical Society, donated in the 1990s by the Wilcox family, was likely made to celebrate a family tree. Another was made by one Abbie (Abigail) Wilcox of North Thetford while she was a student at Thetford Academy. These wreaths were made in the spirit of honoring family and incorporated hair from family members who were living. Abbie died in 1971 at the age of 100. So she would have been making that hair wreath in the very late 1800s.

As society became more mechanized, photography became the way to capture and immortalize family members. The art of hair work faded away in the early 1900s.

Photo credit: Li Shen, except where noted