A bountiful deer season, but are ticks, COVID part of the picture?

While deer evidently spread COVID among themselves, the odds of a hunter contracting COVID from a deer seem minuscule

Bright yellow boards on display in the Thetford Center Village Store speak of the successes of local hunters in the 2021 deer Rifle Season. The boards exhibit the statistics: name of hunter, town, date and time of day they bagged their deer, plus its sex, number of antler points, and weight. The Village Store is one of 16 big game reporting stations in Orange County. Others nearby are Coburn’s Store in Strafford and Wing’s Market in Fairlee. Along the side of the building hangs a scale for weighing the carcasses. Hunters who take deer, bear, or turkey are legally required to report them within 48 hours and to attach the tag they obtained with their hunting license. Reporting by hunters is a critical source of information for the VT Fish and Wildlife Department on the health of game populations and the outcome of game management strategies.

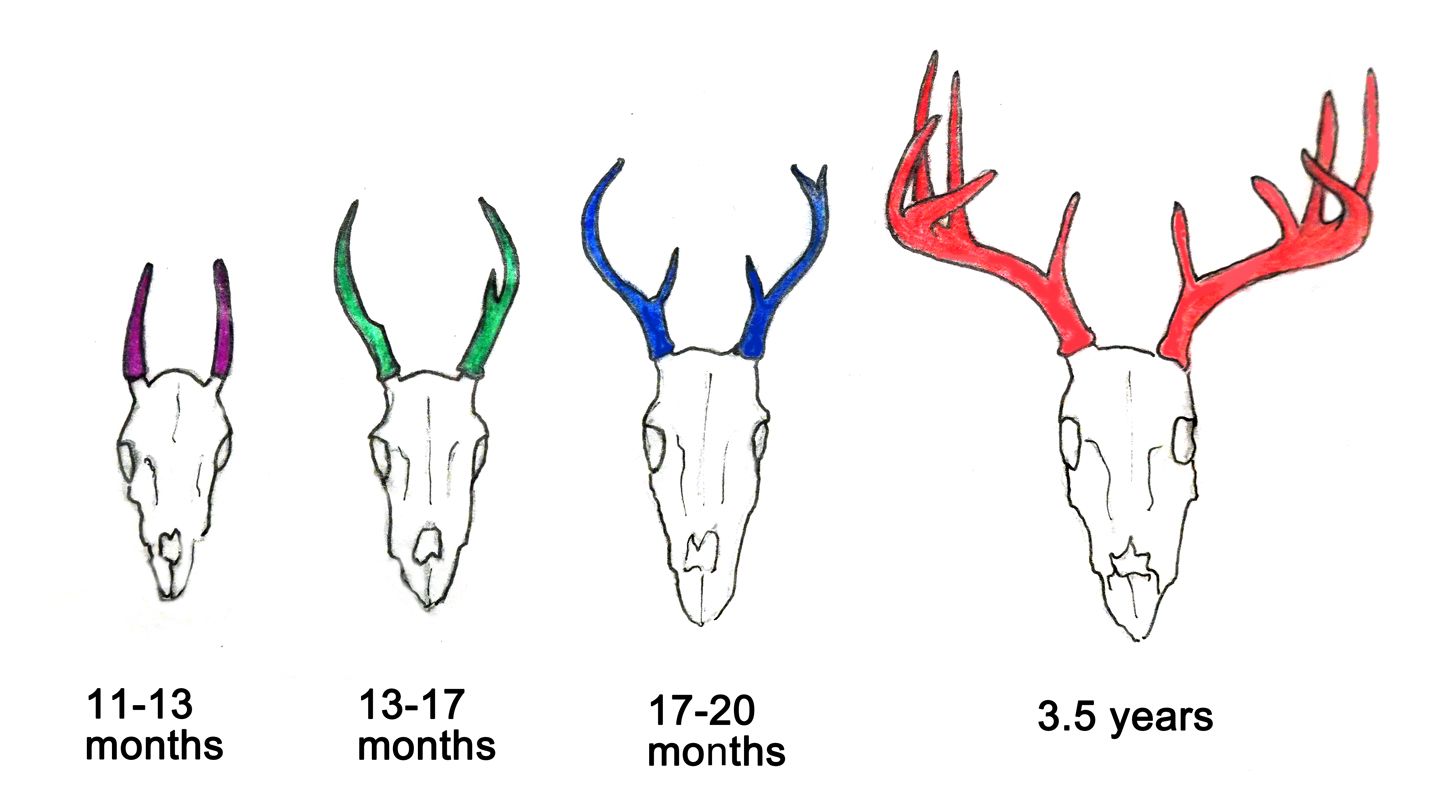

Ellis Paige, our wellspring of local lore, has hunted for decades on his land that’s no more than a mile away from the village. He noted that the number of deer taken is up this year. Moreover, their weight and the number of antler points has increased from a few years ago. He thought this was probably a result of the ban on shooting spikehorns, a controversial measure first instituted in 2005 but recently lifted. Spikehorns are bucks, generally in their first year or so of life, that have unbranched antlers referred to as spikes. Older bucks grow antlers with more tines or points. The state is also allowing an increased number of does to be taken to manage the overpopulation of deer in certain areas.

Ellis is replete with hunting stories. He used to enjoy “search hunting” — covering miles of woodlands on foot in hope of spotting a legal deer. And he got really good at it, reminiscing that he would walk quietly, guided by local knowledge of deer habits, till he caught sight of the antlers of a bedded-down buck. Patiently he would wait until the animal stood up — they only lie down for “an hour at a time” — then he’d swiftly take aim and fire. After the excitement came a lot of work. Frequently the bucks were almost heavier than he could drag by himself. One memorable buck was so big he could not budge it at all. He walked home and called neighbor Amy Vance. Even with the towing harness Amy brought, one person could not move this buck. It took two of them heaving it by the antlers in 15-foot stints that left them winded, working in and out of brush to reach the side of the road. Lifting it onto the bed of the truck was out of the question. Ellis, always observant, noticed a nearby bank beside the road. He carefully backed the truck into the bank. In one final effort they hauled the buck to the top of the bank and loaded it without incident. Nowadays, slowed by arthritis, he hunts from a blind he constructed on his land. And he always gets his deer — this year a respectable 7-pointer weighing 157 pounds.

Interestingly, a few days after this buck was bagged, another buck showed up to claim the vacated territory. Ellis found its tell-tale signs, freshly rubbed-off tree bark and broken branches. Bucks perform this ritual to mark their territory, proclaim their dominance, and warn off other bucks that would compete for does. There is a visual and olfactory component to rubs. As well as using antlers to conspicuously mark a tree by destroying the bark, a buck smears his scent on the tree from glands on his forehead. Research indicates this scent contains hormone-like compounds (pheromones) that stimulate estrus in does, preparing them for breeding. It may also suppress aggressiveness and delay rut (the urge to mate and associated behavior) in young bucks, thus imparting a social order among deer in the area. Mature bucks create most of the rubs, while the most frequent visitors are breeding-age does and young bucks. Does in particular spend some time sniffing, rubbing, and even licking.

Bucks also advertise themselves with scrapes in the ground. On encountering a prominent branch overhanging a field edge or trail, they rub it with their facial scent glands, then paw and scrape the ground beneath and urinate there. This again serves to distribute their scent and communicate dominance within their territory.

While handling this year’s buck Ellis noticed that its belly and inner legs were studded with ticks, large and small. Ticks spend most of their lives in solitude, but they must come together to mate, and they frequently do so on large, warm-blooded animals like deer. Along with helping ticks to congregate en masse, a large host offers a generous amount of blood to nourish female ticks, allowing them to produce thousands of eggs. Deer are not the primary reservoir for Lyme Disease and anaplasmosis. We can thank white-footed mice for that. But they facilitate tick reproduction. Ellis was careful to check himself for ticks and hung the deer outside till the unwelcome hitch-hikers dispersed.

While ticks are a well-documented hazard associated with deer, there’s a new concern. Deer in the Midwest and the Northeast are testing positive for COVID. The most dramatic observation was from analysis of samples from over 300 road kills and deer taken by hunters in Iowa. The deer’s neck lymph nodes were collected for routine testing for Chronic Wasting Disease. In addition, researchers performed PCR testing for COVID 19. This method detects the genetic code of the virus and, thus, the presence of the virus itself. They found that in December 2020, 80% of the tested deer were carrying COVID. The accuracy of PCR allowed identification of different viral strains and showed that they were the same as those circulating in people at that time. This suggests that multiple infections from humans to deer had occurred. If it came from a single incident, there would be just one strain of the virus in deer. Evidence of COVID has also been found in samples from deer in Michigan, Illinois, Pennsylvania, and New York. Of 68 deer samples in NY, 19 individuals, or 28%, were positive. Both NH and VT are testing for COVID in deer this season.

It is thought that deer may be exposed to COVID in exurban settings where a high concentration of deer live in close proximity to human habitation. Interestingly, there was no sign of illness in the sampled deer. In other words, they are asymptomatic carriers, and unfortunately, a reservoir of the virus. This concerns public health officials, since viruses have the potential to mutate in a new host and even incorporate genetic material from other viruses carried by animals, producing novel and possibly more dangerous strains of COVID.

While deer evidently spread COVID among themselves, the odds of a hunter contracting COVID from a deer seem minuscule, according to the VT Department of Fish and Wildlife. They advise sensible precautions, like wearing gloves and avoiding cutting oneself while dressing a carcass. Meat should be cooked to at least 165 degrees F to kill all infectious organisms, and, please, don’t consume the lungs or trachea.

Photo and graphic credit: Li Shen