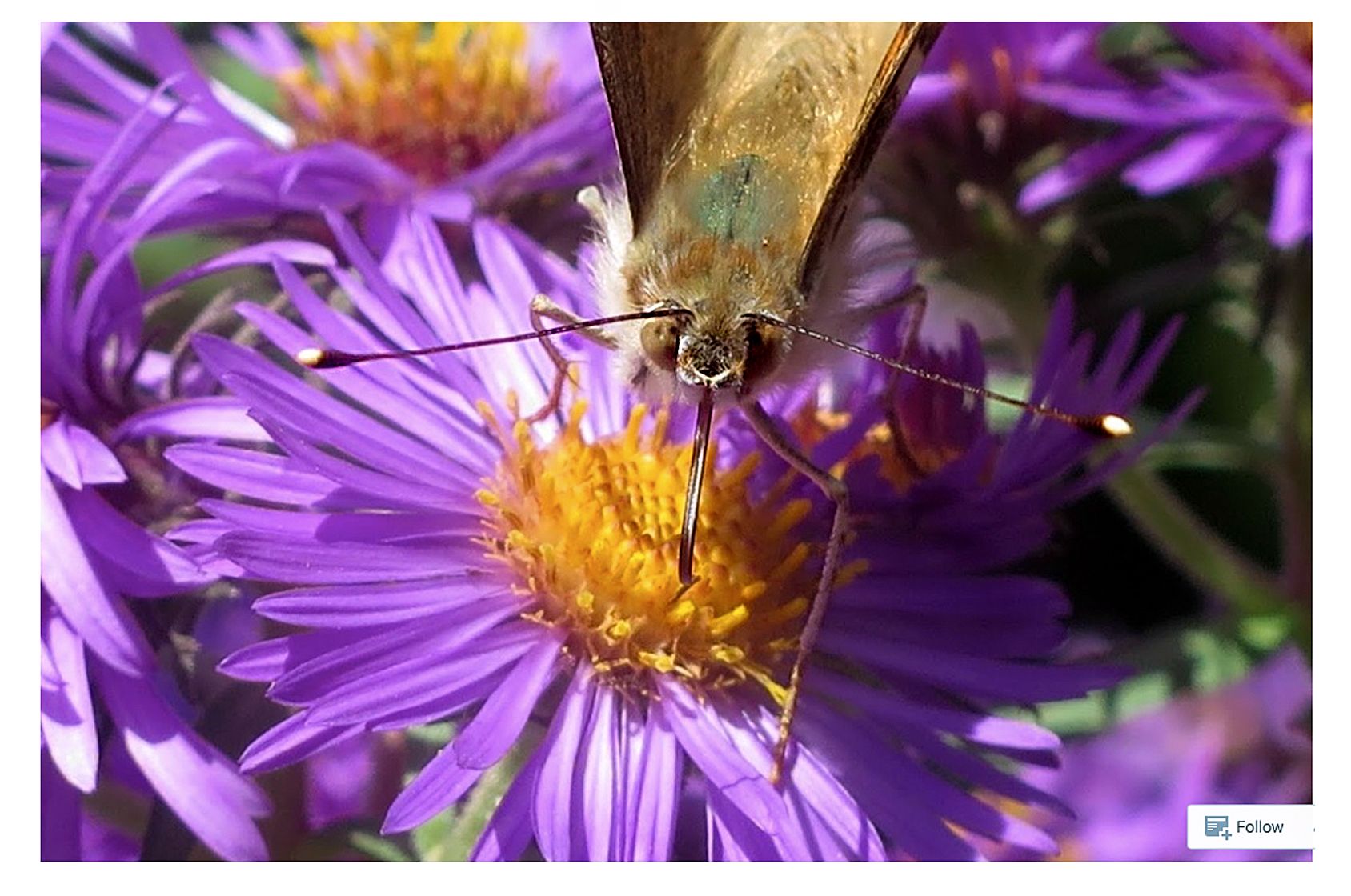

A passion for pollinators and more

Use Zoom to attend the first class in series called "gardening with native plants to bring back the animals that we love."

If people were asked whether they would like their yards to better support pollinators and nature, the overwhelming response around here would probably be “Yes.” And that is echoed outside of Vermont too. In 2019, nine percent or 23.1 million adults in the US converted part of their lawn to natural or wildflower landscapes. It’s a trend that’s coming none too soon. The total acreage of the US covered by lawns — 40 to 50 million acres — surpasses the area allotted to growing irrigated corn and almost equals all national parks combined. According to the EPA, lawns consume 59 million pounds of pesticides a year and almost 3 trillion gallons of water.

Hopefully Thetford won’t fall behind in the call to convert. Certainly not if it were up to Alicia Houk, who moved to Thetford last year from Iowa where she taught environmental sciences — a connection she still maintains through remote classes. Alicia’s real passion, however, is helping nature to recover, sometimes from decades of degradation, by appealing to our sense of beauty. In her short time here she’s already taught a Dartmouth Osher class on gardening for pollinators and has begun installing pollinator gardens showcasing native flowering plants around the Upper Valley.. Her projects are springing up at places like the Lebanon Public Library and the Kilton Library in West Lebanon.

Alicia’s fascination with nature began during childhood summer vacations in the hill county of rural Texas, a respite from her urban life in St Louis, Missouri. Without the distractions of telephone and television, she was free to explore, visit the nearby creek daily, and generally immerse herself in the outdoors. Her most vivid memory of that time were the “singing insects” — a wall of sound that engulfed her as soon as she stepped out of the car. That’s also the place where she grew her first garden.

Even after those summers ended (and the owner eventually sold the land and its summer cabins), the memory remains powerful. Later, in her college years, Alicia’s interest in insects was re-ignited by happenstance. While working at a camp in Maine, she ran across a huge illustrated book on insects in the camp library. Enthralled, the book became her nightly companion.

A renewed desire to work in the outdoors led her to switch studies from English to Biology and to working seasonally at various National Parks out west as a biology research technician. Many of the projects examined the effects of prescribed fire on vegetation, either through plant surveys or tracing historic fires through their lasting effects on trees and soils. One summer spent controlling invasive plants by hand-pulling gave her plenty of hours in which to contemplate the relationship of humans to the natural world. Twenty years later she still muses on the conundrum of invasive species. They are becoming widespread and eradication seems unrealistic, however she has faith that humanity can make a multi-generational commitment to keeping them out of our most ecologically sensitive areas.

A stint in graduate school in Missouri doing research on solitary bees — species that, unlike honeybees, do not create colonies — convinced her to seek a career in public education about conservation and led to her teaching position in Iowa. And soon after arriving in the Upper Valley she made a connection to Osher at Dartmouth, where she offered a class on gardening for pollinators. It was quickly filled. She hopes to teach it again this fall, at the time when gardeners start planning for the next year.

There’s more - coming right up on this Monday, March 14th at 6:30 pm. The Thetford and West Fairlee Conservation Commissions, via Zoom (meeting link), will sponsor the first class of Alicia’s series on “gardening with native plants to bring back the animals that we love” that will feature some hands-on sessions as the weather warms.

Alicia believes that if people can be convinced to put time, energy, and resources into maintaining a lawn, then they can also be convinced to trade it for something more rewarding and beautiful - a swath of native wildflowers. The lawn is a “cultural norm” that originated through imitation of the great estates of the English aristocracy who owned so much land (at the expense of the peasantry) that they could afford to waste it on lawns. But ecologically speaking, a tidily mown lawn is akin to a desert. It contains a few species of imported grass that offer no flowers and little sustenance for native insects or animals. In fact humans have removed flowers from much of the landscape through mowing and conversion of vast areas of land to agriculture that are all too often sprayed with pesticides (3.5 million metric tons, that's 3.8 million US tons, in 2020, worldwide). We’re now experiencing a global decline in insect biomass of 10-20% per decade and are faced with its profound ecological implications. In addition to their vital service of pollination, insects are a critical link in the food chain between plants and higher creatures, including birds, amphibians, and many mammals.

It may take a movement, like the Victory Gardens of World War II, to raise public appreciation of the natural world and its current, dire state and to establish a new normal of natural gardening. Alicia and many others around the country are ready to take on that challenge.

Find more from Alicia on her blog: https://awildgarden.com

Photo credit: Alicia Houk