The anatomy of the Post Mills Landfill

"The unique situation of the Landfill,... presents a threat ..." What happens next is the subject of ongoing discussions.

On Monday June 3rd the Thetford Selectboard had the pleasure of a conversation with John Brabant, a hydrogeologist by training, who was intimately involved with the closure of the Upper Valley Regional Landfill (UVRL) in Post Mills.

Townspeople are so accustomed to the existence of the landfill that we don't question why it came to be there. John filled in the Selectboard on a little of its background.

The landfill had its beginnings as a gravel pit in the oxbow of the Ompompanoosuc River in Post Mills. Historically, deposits of sand and gravel were formed when the glaciers melted at the end of the Ice Age. As the ice retreated northward, lakes formed in many of the valleys in Vermont. Streams entering the lakes deposited sand and gravel in deltas or shoreline beaches. Judging by the many occurrences of sandy and gravelly areas along the river, the Ompompanoosuc Valley was a narrow lake connected to Lake Hitchcock.

The owners of the gravel pit that became the UVRL extracted gravel for some years. They also ran a trash hauling and disposal business. When they could no longer profitably mine gravel, they began filling the hole with farm trash. This soon turned into a business, and in 1971 the gravel pit obtained its first permit to become a landfill that accepted trash from Thetford and surrounding towns like Fairlee, West Fairlee, and Lyme.

In the past the usual method of trash disposal had been “over the bank” or by open burning, a dirty and polluting method that was endorsed by the Department of Health because the biggest perceived threat posed by trash was infestation by rats. John said that in his town, at the end of a day's trash dumping, a heap of old tires was piled on top, doused with diesel fuel, and set ablaze. It certainly took care of the rats.

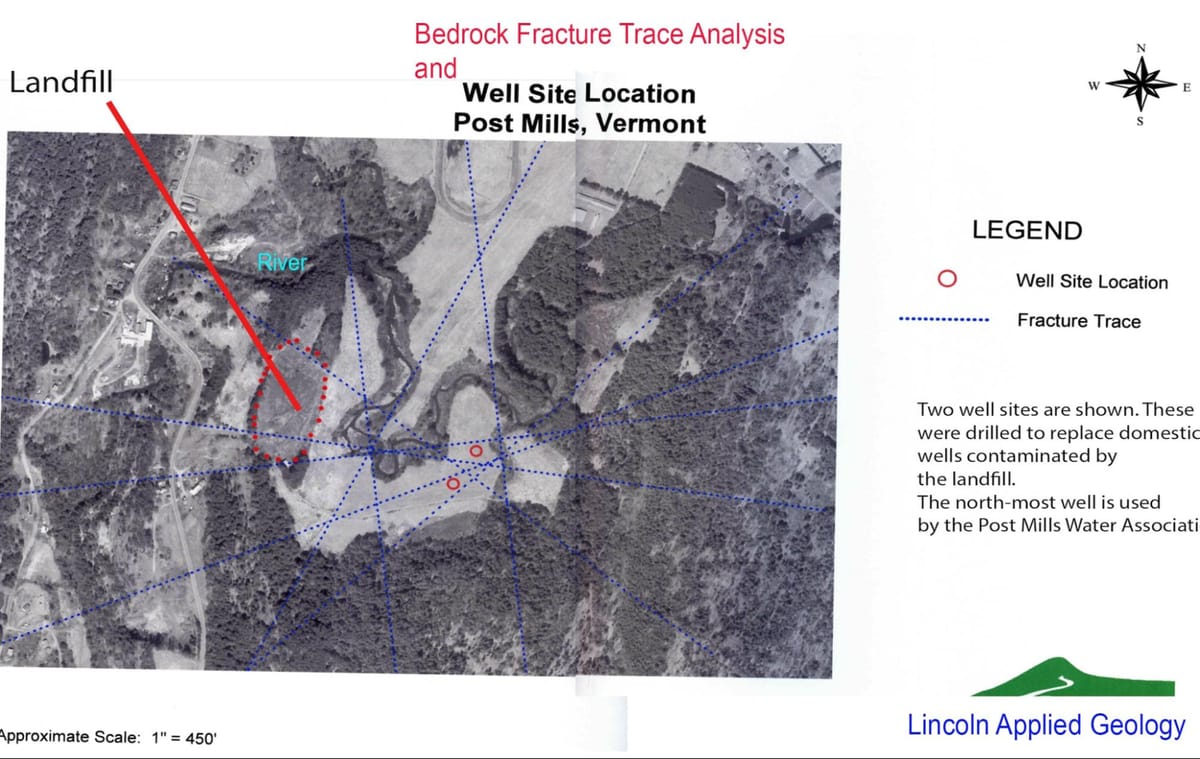

Thus a landfill where the trash was compacted and buried at the end of the day instead seemed a much better solution. But in Post Mills there was a significant downside to this. Gravel soil has high hydraulic conductivity. The tiny interconnected spaces (pores) in the gravel allow water to move through more easily than in other soil types, and gravel soils store a lot of water in their pores. The ability to convey and store water makes gravel a favorable soil type in which to dig a well. And because the gravel reportedly had been mined down to bedrock, there would have been nothing between the trash and fractures in the bedrock that also carry water. These bedrock fractures are the source of water for deep drilled wells.

Thus when the gravel pit began filling with trash, the wells on neighboring properties became contaminated early on.

Nevertheless, in 1982 the state issued a permit for continued use of the landfill until 1986, which included the condition that the landfill corporation provide "an acceptable alternate source of drinking water ... for those residences and property in the vicinity of the landfill … the present water supplies of which may become adversely affected by the landfill." The replacement water supply did not come online until 1988.

Meanwhile a big change had come to the world of trash in 1987 when Act 78 was adopted. Because of increasing concerns about the environment, Act 78 required that "New landfills placed in operation after July 1st, 1987 must be lined and must include leachate collection and treatment systems." and that "No later than July 1991, the operating portion of most landfills must be lined."

Throughout Vermont, landfills began to close. But the state allowed UVRL to remain open, taking trash from most of Vermont. Moreover, the state had always allowed the landfill to accept what was known as "household hazardous waste." According to the Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC), "Household Hazardous Waste (HHW) includes any household product labeled: caution, toxic, danger, hazard, warning, poisonous, reactive, corrosive, or flammable." On top of that, it was also legal to dump farm trash in the landfill. Between these categories, anything from chemicals like paint stripper to barrels used for pesticides were undoubtedly deposited. By contrast, a commercial operation is not allowed to dispose of these exact same products in a municipal landfill. They are mandated to handle them as hazardous waste.

In 1990, volatile organic compounds — a signature of landfill contamination — were found in the replacement water supply.

In 1991 the state District Environmental Board denied the landfill corporation's application for an Act 250 permit to continue to dispose of waste in the landfill. However, the landfill went on taking trash, and there was no enforcement against this by the state, presumably because there was nowhere else in Vermont for the trash to go.

In 1995 a neighboring deep-drilled well near the replacement water supply also tested positive for landfill contaminants.

But it was not until 1998, after years of litigation, that the DEC issued an Administrative Order mandating that the landfill be closed and capped and that "within 24 months" the contaminated water supply be replaced with a new source compliant with Well Isolation Zones under the Vermont Water Supply Rule. The landfill closed in 1998.

The structure of the landfill cap is described in the Post-Closure Plan of 2002: "The landfill was reshaped and capped with a multi-layer final cover system consisting of: a layer of soil of varying depth to cover any exposed waste and to provide a uniform surface, a 6" gas vent layer, a geosynthetic clay liner, a 40 mil linear low density polyethylene liner, a geotextile lined geonet, a 12'’ earthen drainage layer, a 6" vegetative layer, and a 6" topsoil layer. A gas vent system was also installed to allow for the release of landfill gas."

While the impervious plastic prevents rainwater from infiltrating the trash from above, the UVRL is still an unlined landfill. The state described the situation thus: "The unique situation of the Landfill, an unlined landfill containing unknown quantities of potentially hazardous materials, situated on coarse overburden (gravel) and fractured bedrock in close proximity to residences and downgradient of residential water supplies, presents a threat .…"

Moreover, the river lies in close proximity and is very likely connected hydrogeologically via the "coarse overburden" to the water table around the landfill. During high water events such as after heavy rain, the river rises, while in droughts it falls. This would result in ground water rising and falling, around and probably inside the landfill.

In the depths of the landfill, things are not static. Depending on the availability of oxygen, water, and heat, bacteria can break down the chemical bonds in many materials so they disintegrate. The by-product is landfill gas which is a roughly 50:50 mix of methane and carbon dioxide with traces of nitrogen. At the UVRL, white stand pipes allow the gas to be released.

While many of the organic compounds, like solvents from paint stripper, etc. have degraded, one class of toxic chemical, PFAS, stands out as a permanent threat. PFAS — aka “forever chemicals” — do not degrade, and because the landfill was not capped for many years, a plume of contamination has seeped from the landfill into the bedrock aquifer, moving to the southwest. The EPA ruled that there is no safe level of PFAS in drinking water.

As the volume of the garbage decreases with decomposition, the cap is slumping in places. It is periodically inspected and maintained by the state Solid Waste Management Program (SWMP) as part of its Post Closure Plan. Also as part of the Plan, the level of contaminants in the groundwater is monitored in a selection from five bedrock monitoring wells and three overburden wells. While the Post Closure Plan expired in 2022, the SWMP continues to monitor the landfill under the Administrative Order of 1998, which will expire in 2028. What happens next is the subject of ongoing discussions, and the Selectboard is scheduled to meet with representatives from the Agency of Natural Resources at 7:00 pm on Monday June 10th.