Multiflora rose - it's pretty .... invasive

At least in Thetford, we do not yet have monocultures of multiflora rose. But the time to control it is now.

Anyone driving on Rt 132 from Norwich to Thetford last week would no doubt have admired the abundant sprays of white flowers adorning bushes scattered along the road. And in Thetford, too, they made an appearance on Tucker Hill Road and elsewhere, before downpours scattered their petals.

What we are seeing is the spread of a non-native, invasive species called multiflora rose. The existence of this rose species in the US is a continuation of the long story of humanity's fascination with roses — a love affair that began 5,000 years ago in Asia and the Middle East. In China, members of the Han dynasty became so obsessed with roses that they cultivated parks devoted to this flower, taking over enough land to threaten the food supply. Early Phoenicians, Greeks, and Romans grew, studied, and traded in roses and distributed the plants everywhere they traveled and conquered. As a result, roses (and rose scented products) spread throughout the Middle East and Mediterranean. In Egypt Cleopatra is reputed to have filled her chamber with two feet of rose petals plus a fountain of rose water to win the affection of Mark Anthony. Centuries later in Rome, emperors bathed in rose water and sat on carpets of rose petals at feasts. Peasants were forced to grow roses instead of food to satisfy this demand.

Roses may have come to the rest of Europe with Alexander the Great, who reputedly brought roses with him as he conquered. He also sent back any new varieties he discovered to his home region of Macedonia. During the Dark Ages, when famine, war, and disease swept Europe, monasteries became the repository of knowledge about roses and their cultivation. By the 17th century, roses were valued so highly that rose water and roses were equivalent to currency and were used to pay off certain kinds of debt.

European settlers brought their love of roses to North America. The rose was favored by many American presidents. George Washington grew them at his Mount Vernon estate, John Adams planted the first rose at the White House, and Woodrow Wilson established the formal rose garden that exists there to this day.

The rose is now one of the most popular flowers in the US, which means the demand for rose bushes is high, and professional rose growers seek the most efficient ways to produce more. Since roses do not breed true from seed, desirable rose varieties are multiplied by grafting a bud-eye onto the rootstock of another rose. This is more cost-effective than growing them from cuttings, because a cutting requires three to four bud-eyes, whereas a graft uses just one.

Multiflora rose was imported to the US from Japan in 1866 for that very purpose. It grows vigorously and is hardy down to temperatures in the -20 degrees F. It also serves as a useful monitor for mosaic virus infection in grafted bud-eyes, since it will show severe symptoms with even the mildest virus infection.

Unfortunately, the use of multiflora rose did not stop there. In the 1930s the US Soil Conservation Service began using it for erosion control. It was also promoted as a living fence since it forms a dense, thorny barrier impenetrable to livestock. Root cuttings of multiflora rose were distributed to landowners through State Conservation Departments as it provides cover for game species — pheasants, bobwhites, and cottontail rabbits — and food for songbirds.

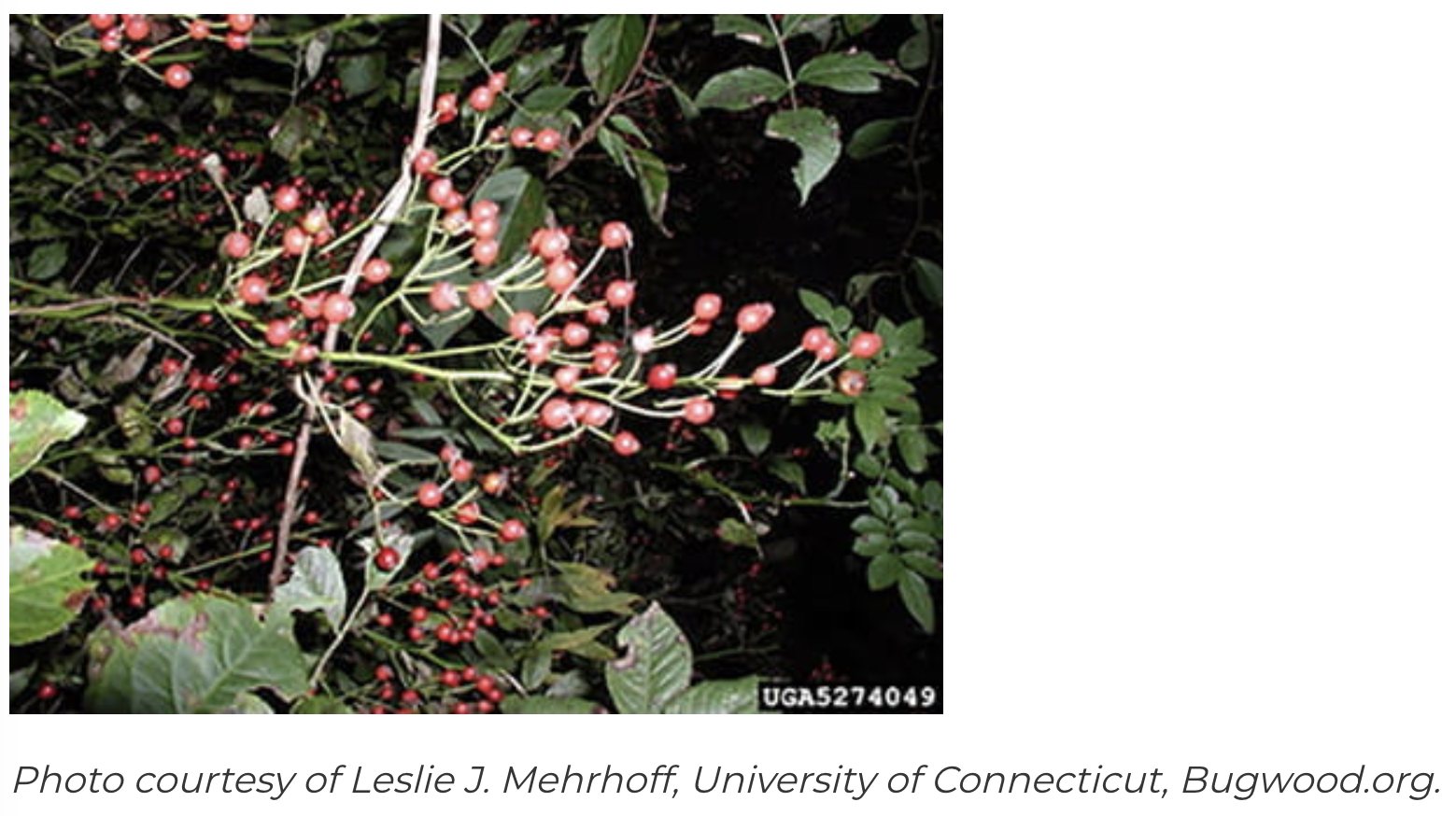

The showy flowers are grouped on branching stems or panicles, and every branch on a large bush can support 40-50 panicles, each giving rise to as many as 100 small rose hips. One rose hip contains up to 21 seeds. Thus one bush may produce 500,000 seeds in a year.

The rose hips are eaten by birds that disperse the seeds in their droppings. Germination rate is high, and the seeds remain viable in soil for up to 20 years. This prolific trait, combined with the aptitude of its branches to take root, allows it to make dense thickets that choke out native plants, especially in fields, pastures, open woodlands, and edges of forests and wetlands. It is an aggresive invasive plant that is not affected by any pests or diseases native to the US.

At least in Thetford, we do not yet have monocultures of multiflora rose. But the time to control it is now. Frequent cutting, three to six times in the growing season, has been shown to effectively eliminate it in two to four years, because every time the plant is cut and forced to sprout it reduces the reserves in the roots and weakens the plant. However a single cutting is counterproductive as it encourages the bush to grow more sprouts, and so more fruiting branches. In July, August, and September the bushes can be controlled by reducing them to a one-inch stump and immediately treating it with glyphosate. Roundup "Poison Ivy Killer" has been shown to work well. A licensed professional can be employed to apply a foliar herbicide spray to a large infestation.

Contrary to assumptions about its benefits, multiflora rose is not good for the environment because it forms ever-increasing stands that reduce the species diversity and richness of native plants. This reduction in plant diversity can threaten some species that are already at risk. It also changes the structure of habitats it invades and makes conditions less hospitable for many animals and ground- and shrub-nesting birds.

While some websites attribute curative properties to multiflora rose, this is not a good reason to keep it around. There are other medicinal roses, like cabbage rose, that do not wreak environmental damage.